My first encounter with the city of Istanbul goes back to 1971. It was brief but decisive.

At the beginning of a very long journey through Turkey, a country at the time considered dangerous, I stopped for a few days in Istanbul, but took no photos there, as I was saving what films I had for Eastern Anatolia, a region which seemed to me to hold more mystery. However, whilst out walking in search of little known Byzantine churches, I strayed into the squalid but extremely fascinating quarters of the Golden Horn. There I witnessed two street scenes which affected me profoundly. The first was quite amusing; in a filthy alleyway two children dressed in rags were bombarding each other enthusiastically with mud, looks of pure joy on their faces. The other was more tragic: a few minutes later, in the main street of Fener, I saw a young apprentice, who had just been injured by a machine, being loaded into a decrepit dolmuş, his complexion pale, blood mixed with dirty oil, suffering, resignation, solidarity. Instantly, I felt drawn by this town and knew that its hold over me would remain for many years to come.

The following year, thanks to a study grant from the Turkish government, I retuned to Istanbul for two whole months, during which I took my very first black and white photographs. After that, annual visits, some short and some longer, culminated in a period of residence in Istanbul which lasted nearly three years. Initially, I worked as a teacher and then later as a photographer for the French Institute of Anatolian Studies. Throughout these years I roamed the city streets, tirelessly, my camera to hand ready to capture something new and completely unexpected. Fascinated by the layout of this thronging city with its back alleys and its wastelands, my explorations led me into factories and workshops where I felt strangely at home, establishing instinctive relations with the usta.I would spend days on end in the çay evi, make daily visits to the barbers and spend evenings in the lokanta, but I would also have to queue for hours in administrative offices trying in vain to get my residential papers in order. And the photographs accumulated.

The 1980 coup d'etat marked the beginning of a period of official vandalism: the ancient quarters of the city were systematically torn down by administrators ignorant of their valuable heritage. The ancient, the historic and the simply charming crumbled under the assault of bulldozers. I too physically shuddered under this violation; each time I left Istanbul and returned to Lyons, I vowed that it would be the last time!

And yet, back I come. Again and again.

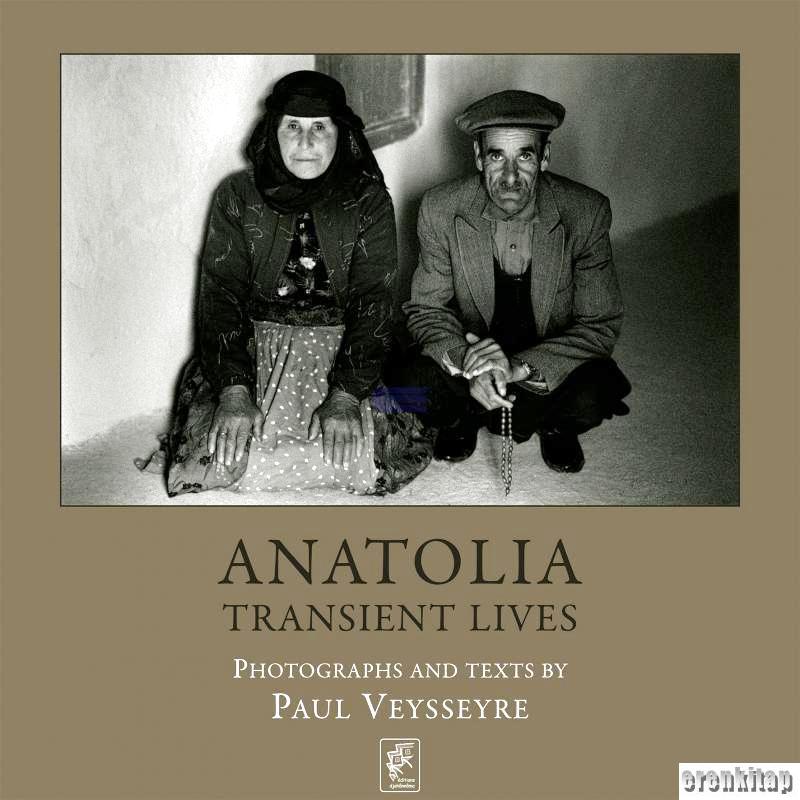

Taken between 1972 and 1991, Paul Veysseyre's photographs sketch a timeless portrait of İstanbul's daily life and also of its more hidden aspects.